Understanding Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis involves narrowing spaces within your spine, compressing nerves and potentially causing pain, numbness, or weakness. It’s often linked to age-related wear and tear.

The condition frequently stems from osteoarthritis, where cartilage breakdown leads to bone spurs and thickening of ligaments, reducing spinal canal space.

Approximately 75% of individuals experience some form of back or neck pain, but most recover without surgery, emphasizing conservative management approaches.

Neural foramina narrowing, the openings where nerves exit the spine, contributes to stenosis, impacting nerve function and causing radiating symptoms.

Managing spinal stenosis often focuses on repositioning the spine to alleviate pressure on nerves, utilizing exercises and lifestyle adjustments effectively.

Leg pain intensifying during walking and easing with rest can indicate spinal stenosis, requiring evaluation by a spine specialist for diagnosis.

What is Spinal Stenosis?

Spinal stenosis is a condition characterized by the narrowing of spaces within the spine, which can put pressure on the spinal cord and nerves. This narrowing doesn’t necessarily happen throughout the entire spine; it often affects specific areas, leading to varied symptoms. The term “stenosis” itself simply means narrowing of a passage within the body.

Essentially, the spinal canal, which houses the delicate spinal cord, or the neural foramina – the openings where nerves exit – become constricted. This compression can disrupt nerve function, resulting in pain, numbness, weakness, or tingling sensations that radiate into the arms or legs. It’s crucial to understand that the severity of symptoms doesn’t always correlate directly with the degree of narrowing observed on imaging.

While it can occur at any level of the spine, lumbar spinal stenosis (lower back) and cervical spinal stenosis (neck) are the most commonly affected regions. Often, the narrowing is a gradual process, developing over many years due to age-related changes like osteoarthritis.

Causes and Risk Factors

The most prevalent cause of spinal stenosis is osteoarthritis, the wear-and-tear of cartilage within the spine. As cartilage deteriorates, bone spurs can develop, and ligaments thicken, encroaching upon the spinal canal. Other contributing factors include herniated discs, spinal injuries, and, less commonly, tumors or growths within the spine.

Several risk factors increase susceptibility to developing this condition. Age is a significant factor, as the degenerative changes associated with aging are primary drivers. A family history of spinal stenosis also elevates risk, suggesting a genetic predisposition. Prior spinal surgeries or injuries can create instability and contribute to narrowing.

Furthermore, certain congenital conditions, present at birth, can result in a smaller spinal canal, predisposing individuals to stenosis later in life. Maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding activities that excessively stress the spine can help mitigate some risk factors.

Types of Spinal Stenosis

Spinal stenosis isn’t a uniform condition; it manifests differently depending on the affected spinal region. Cervical spinal stenosis, occurring in the neck, can compress the spinal cord directly, potentially leading to neck pain, shoulder weakness, and even issues with hand coordination. Lumbar spinal stenosis, affecting the lower back, is the most common type, often causing leg pain (sciatica) that worsens with walking and improves with rest.

Thoracic spinal stenosis, impacting the mid-back, is the least frequent form. Symptoms can include back pain, numbness in the legs, and, in severe cases, bowel or bladder dysfunction. The specific symptoms depend on the severity and location of the narrowing within the spinal canal.

Diagnosis involves imaging techniques like MRI or CT scans to pinpoint the location and extent of the stenosis, guiding appropriate treatment strategies tailored to the specific type and individual needs.

Cervical Spinal Stenosis

Cervical stenosis (CS) specifically refers to the narrowing of the spinal canal within the neck region. This narrowing can compress the spinal cord and nerve roots, leading to a range of symptoms. Common indicators include neck pain that may radiate into the shoulders and arms, as well as weakness, numbness, or tingling in the hands and fingers.

In more severe cases, cervical spinal stenosis can affect balance and coordination, and even impact bowel or bladder control. Diagnosis typically involves imaging studies like MRI to visualize the spinal cord and identify the area of compression. Treatment approaches vary depending on the severity of the stenosis, ranging from conservative measures like physical therapy to surgical intervention.

Careful evaluation is crucial to determine the best course of action for managing this condition and alleviating symptoms.

Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Lumbar spinal stenosis affects the lower back, causing narrowing of the spinal canal in that region. A hallmark symptom is neurogenic claudication – leg pain that worsens with walking and improves with rest or leaning forward. This occurs due to compression of the nerves in the lower spine. Individuals may also experience numbness, weakness, or cramping in the legs and feet.

Diagnosis often involves a physical exam and imaging tests like X-rays or MRIs to pinpoint the location and extent of the narrowing. Treatment strategies range from conservative approaches, such as physical therapy and pain management, to surgical options in more severe cases. The goal is to relieve pressure on the nerves and improve function.

Managing symptoms effectively is key to maintaining quality of life.

Thoracic Spinal Stenosis

Thoracic spinal stenosis, affecting the mid-back, is less common than lumbar or cervical stenosis. Symptoms can be subtle and may include pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs, and in severe cases, even bowel or bladder dysfunction. This arises from narrowing within the thoracic spine, compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Diagnosis typically involves imaging studies like MRI to visualize the spinal canal and identify the source of compression. Treatment approaches vary depending on the severity of symptoms and may include physical therapy, pain medication, or, in rare instances, surgical intervention to decompress the spinal cord.

Careful monitoring and management are crucial for optimal outcomes.

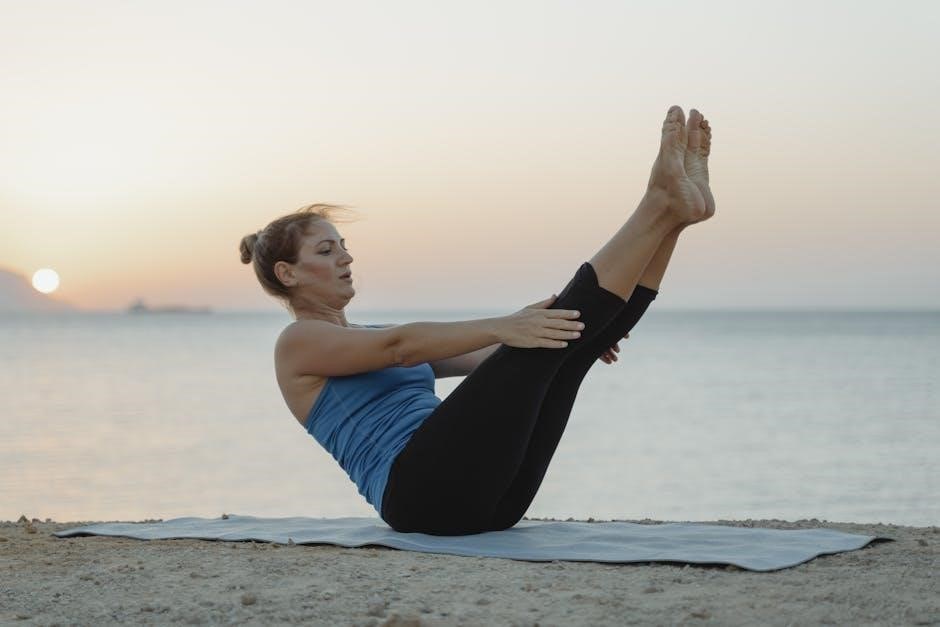

Exercises for Spinal Stenosis: A Comprehensive Guide

Exercises aim to alter spinal positioning, relieving nerve pressure and improving function; a tailored program, guided by a professional, is essential for safety.

Goals of Exercise for Spinal Stenosis

The primary goals of exercise for spinal stenosis are multifaceted, focusing on symptom management and functional improvement. These exercises aren’t about “curing” the stenosis, but rather optimizing your ability to live with it comfortably and maintain an active lifestyle.

Central to this approach is reducing nerve compression, achieved through movements that create more space within the spinal canal. This often involves exercises promoting spinal flexion – gently bending forward – which can temporarily widen the canal. However, extension-based exercises require careful consideration.

Strengthening core muscles is also crucial, providing support for the spine and improving posture. A strong core helps stabilize the spine, reducing strain and potentially minimizing pain; Furthermore, exercises aim to enhance flexibility, particularly in the hamstrings and piriformis muscles, which can contribute to spinal imbalances.

Ultimately, the goal is to improve walking tolerance, reduce leg pain, and enhance overall physical function, empowering individuals to participate more fully in daily activities.

Important Considerations Before Starting

Before embarking on any exercise program for spinal stenosis, several crucial considerations must be addressed to ensure safety and effectiveness. Paramount among these is a thorough consultation with a healthcare professional – a physician, physical therapist, or qualified exercise specialist.

They can accurately diagnose your specific condition, assess your limitations, and tailor an exercise plan to your individual needs. Self-treating based solely on online resources can be risky, potentially exacerbating symptoms.

Equally important is listening to your body. Pay close attention to any pain or discomfort experienced during exercise. Sharp, radiating pain warrants immediate cessation of the activity. Mild soreness is acceptable, but it should not be debilitating.

Gradual progression is key; start slowly and gradually increase the intensity and duration of exercises as your strength and tolerance improve. Avoid pushing yourself too hard, too soon.

Consulting a Healthcare Professional

Seeking guidance from a healthcare professional is the foundational step before initiating any exercise regimen for spinal stenosis. A qualified physician, physical therapist, or certified specialist can provide a precise diagnosis, differentiating between various types and severities of the condition.

This assessment is crucial because exercises beneficial for one type of stenosis might be detrimental to another. They will evaluate your medical history, conduct a physical examination, and potentially order imaging tests like X-rays or MRIs.

Based on this evaluation, they can develop a personalized exercise plan tailored to your specific needs and limitations, ensuring it aligns with your overall health status.

Furthermore, a professional can educate you on proper form and technique, minimizing the risk of injury and maximizing the effectiveness of the exercises. They can also monitor your progress and adjust the plan as needed.

Listening to Your Body

Paying close attention to your body’s signals is paramount when performing exercises for spinal stenosis. Discomfort is expected during exercise, but sharp, radiating, or increasing pain is a clear indication to stop immediately. Ignoring these warning signs can exacerbate your condition and potentially cause further nerve compression.

It’s essential to differentiate between muscle soreness, which is normal after exertion, and pain stemming from nerve irritation. If an exercise consistently provokes pain, even mild, it’s likely not suitable for you.

Start slowly and gradually increase the intensity and duration of your exercises. Don’t push yourself beyond your current capabilities. Rest when needed, and prioritize proper form over completing a certain number of repetitions.

Remember that everyone’s experience with spinal stenosis is unique. What works for one person may not work for another. Be patient with yourself and respect your body’s limitations.

Core Strengthening Exercises

A strong core provides essential support for the spine, helping to stabilize it and reduce stress on the affected areas in spinal stenosis. These exercises should be performed with controlled movements, focusing on engaging the abdominal and back muscles.

Pelvic Tilts are a gentle starting point, involving lying on your back with knees bent and gently rocking your pelvis forward and backward. This improves spinal mobility and strengthens abdominal muscles.

Abdominal Bracing is another foundational exercise. Imagine preparing for a punch to the stomach – tighten your abdominal muscles without holding your breath. Maintain this contraction for several seconds, repeating multiple times.

Consistency is key; aim to incorporate these exercises into your routine several times a week. Remember to listen to your body and stop if you experience any pain.

Pelvic Tilts

Pelvic Tilts are a foundational exercise for individuals with spinal stenosis, gently mobilizing the lower back and strengthening core muscles without excessive strain. Begin by lying comfortably on your back with your knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

Initiate the movement by gently flattening your lower back against the floor, tightening your abdominal muscles and slightly tilting your pelvis upward. Hold this position for a few seconds, focusing on maintaining core engagement.

Slowly release, allowing a small natural arch to return to your lower back. Repeat this rocking motion – flattening and releasing – for 10-15 repetitions.

Focus on controlled movements, avoiding any jerking or forceful actions. This exercise helps improve spinal awareness and promotes better posture, contributing to pain management.

Abdominal Bracing

Abdominal bracing is a crucial core stabilization exercise for those managing spinal stenosis, enhancing support for the spine and reducing stress on affected areas. Unlike crunches, bracing doesn’t involve movement, but rather a sustained muscle contraction.

To perform abdominal bracing, imagine preparing to receive a gentle punch to the stomach. Gently tighten your abdominal muscles as if bracing for impact, without holding your breath or changing your posture.

Focus on drawing your navel towards your spine, engaging deep core muscles. You should feel a firm, supportive contraction around your midsection. Hold this contraction for 5-10 seconds, then slowly release.

Repeat this bracing exercise 10-15 times, gradually increasing the hold duration as your strength improves. This technique helps maintain spinal stability during daily activities.

Flexion-Based Exercises

Flexion-based exercises aim to create more space within the spinal canal by gently bending forward, potentially relieving pressure on compressed nerves – a common strategy for lumbar spinal stenosis. These movements can help open up the foramina, easing discomfort.

However, it’s vital to proceed cautiously, as not everyone benefits from flexion. Individuals with cervical stenosis should generally avoid excessive forward bending. Always listen to your body and stop if pain increases.

Effective flexion exercises include the knee-to-chest stretch, seated lumbar flexion, and a modified child’s pose with sidebending. These stretches gently mobilize the spine and promote flexibility.

Remember to perform these exercises slowly and controlled, avoiding any jerky movements. Focus on feeling a gentle stretch, not pain; Consistent, gentle flexion can improve mobility and reduce stenosis symptoms.

Knee-to-Chest Stretch

The knee-to-chest stretch is a foundational flexion-based exercise for spinal stenosis, particularly beneficial for lumbar stenosis sufferers. It gently encourages spinal flexion, creating space and alleviating nerve compression. Begin by lying flat on your back with knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

Slowly bring one knee towards your chest, clasping your hands behind your thigh or over your shin. Hold this position for 20-30 seconds, feeling a gentle stretch in your lower back and hips. Repeat with the other leg.

For a more advanced stretch, bring both knees to your chest simultaneously. Remember to maintain a relaxed posture and breathe deeply throughout the exercise. Avoid pulling forcefully; let gravity assist the stretch.

This exercise can help improve spinal mobility, reduce muscle tension, and ease lower back pain associated with spinal stenosis. Perform 2-3 repetitions on each leg.

Seated Lumbar Flexion Stretch

The seated lumbar flexion stretch is a gentle yet effective exercise for individuals with spinal stenosis, particularly those experiencing lumbar symptoms. It promotes spinal flexion, aiming to widen the spinal canal and reduce pressure on nerves. Begin by sitting upright on a chair with your feet flat on the floor.

Slowly round your back, allowing your chin to move towards your chest. Reach forward as if trying to touch your toes, maintaining a relaxed posture. You should feel a stretch along your lower back and hamstrings.

Hold this position for 20-30 seconds, breathing deeply and evenly. Avoid bouncing or forcing the stretch. Repeat this movement 2-3 times, gradually increasing the range of motion as comfortable.

This stretch can help improve flexibility, reduce stiffness, and alleviate pain associated with spinal stenosis. It’s a safe and accessible exercise for many individuals.

Child’s Pose with Sidebending

Child’s Pose with Sidebending offers a modified version of the traditional pose, providing a gentle stretch for individuals managing spinal stenosis. Begin on your hands and knees, then sit back on your heels, extending your arms forward. This initial position creates a gentle spinal flexion.

To incorporate sidebending, gently reach one arm towards the side while keeping your hips grounded. You should feel a stretch along your side and lower back. Avoid forcing the movement; listen to your body’s limits.

Hold the sidebend for 20-30 seconds, breathing deeply. Repeat on the other side. Perform 2-3 repetitions on each side, focusing on controlled movements.

This variation can help decompress the spine, improve flexibility, and relieve pressure on nerves, offering a comfortable stretch for those with spinal stenosis.

Extension-Based Exercises (Caution Advised)

Extension-based exercises, involving backward bending movements, require significant caution for individuals with spinal stenosis. While some may find relief, these exercises can potentially worsen symptoms by further narrowing the spinal canal in certain cases.

Prone press-ups are a common example, where you lie on your stomach and gently lift your upper body using your arms. However, this should only be attempted under the guidance of a healthcare professional.

Carefully monitor your symptoms during and after the exercise. If you experience increased pain, numbness, or weakness in your legs or feet, immediately stop and consult your doctor.

Individual responses vary; what works for one person may not work for another. A thorough assessment is crucial before incorporating extension exercises into your routine.

Prone Press-Ups (with caution)

Prone press-ups, performed lying face down, can gently extend the spine, potentially creating more space for nerves – but proceed with extreme caution. Begin by lying prone with forearms on the floor, elbows aligned under shoulders.

Slowly lift your upper body, keeping your hips on the ground, using your arm strength. Only elevate as far as comfortable, avoiding any pain. Hold briefly, then slowly lower back down.

Start with a small range of motion and gradually increase it only if you experience no worsening of symptoms. Frequent repetitions are less important than proper form and comfort.

Monitor closely for increased leg pain, numbness, or weakness. If any of these occur, immediately stop the exercise and consult your healthcare provider. This exercise isn’t suitable for everyone.

Individual tolerance varies greatly; listen to your body and prioritize comfort over achieving a significant range of motion. Professional guidance is highly recommended.

Stretching Exercises

Stretching plays a vital role in managing spinal stenosis by improving flexibility and reducing muscle tension around the spine. Hamstring stretches are crucial, as tight hamstrings can exacerbate lower back pain; perform seated or lying stretches gently.

The piriformis stretch targets the piriformis muscle in the buttock, which can compress the sciatic nerve. Lie on your back, cross one ankle over the opposite knee, and gently pull the uncrossed thigh towards your chest.

Hold each stretch for 20-30 seconds, breathing deeply, and avoid bouncing. Focus on feeling a gentle stretch, not pain. Consistency is key for noticeable improvements.

Regular stretching can help improve posture and reduce pressure on the spinal nerves. Remember to warm up muscles slightly before stretching to prevent injury.

Always listen to your body and stop if you experience any sharp or increasing pain. These stretches complement other exercises for a comprehensive approach.

Hamstring Stretches

Hamstring flexibility is paramount for individuals with spinal stenosis, as tightness can worsen lower back and leg pain. Perform these stretches cautiously and with controlled movements, avoiding any bouncing or jerking.

Seated hamstring stretches involve sitting with legs extended and gently reaching towards your toes, keeping your back as straight as possible. Modify by bending your knees slightly if needed.

Lying hamstring stretches can be done using a towel or strap looped around your foot, gently pulling your leg towards you while keeping it straight. Maintain a neutral spine throughout the stretch.

Hold each stretch for 20-30 seconds, focusing on deep breathing to enhance relaxation and flexibility. Repeat 2-3 times on each leg.

Avoid overstretching, and stop immediately if you feel any sharp pain. These stretches aim to lengthen the hamstrings, reducing strain on the lower back.

Piriformis Stretch

The piriformis muscle, located deep in the buttock, can compress the sciatic nerve in individuals with spinal stenosis, contributing to leg pain and sciatica. Stretching this muscle can provide significant relief.

Supine piriformis stretch: Lie on your back with knees bent and feet flat; Cross your affected leg over the opposite knee. Gently pull the uncrossed thigh towards your chest until you feel a stretch in your buttock.

Seated piriformis stretch: Sit in a chair and cross your affected leg over the opposite knee. Lean forward from your hips, keeping your back straight, until you feel the stretch.

Hold each stretch for 20-30 seconds, breathing deeply. Repeat 2-3 times on each side. Avoid bouncing or forcing the stretch.

Listen to your body and stop if you experience any sharp pain. Consistent piriformis stretching can help alleviate nerve compression.

Low-Impact Aerobic Exercise

Low-impact aerobic exercise is crucial for managing spinal stenosis, improving cardiovascular health without exacerbating spinal compression. It enhances blood flow to nerves and muscles, promoting healing and reducing pain.

Walking is an excellent starting point. Begin with short, slow walks on a flat surface, gradually increasing duration and pace as tolerated. Proper footwear and posture are essential.

Water aerobics offers buoyancy, reducing stress on the spine. The water provides resistance for strengthening muscles, improving flexibility, and minimizing joint impact.

Stationary cycling, with a properly adjusted seat height, can also be beneficial. Avoid leaning forward excessively, maintaining a neutral spine position.

Aim for 30 minutes of low-impact aerobic exercise most days of the week. Always listen to your body and stop if you experience increased pain.

Walking

Walking stands as a foundational low-impact aerobic exercise for individuals managing spinal stenosis, offering numerous benefits with minimal strain on the spine. It’s easily accessible and requires no specialized equipment, making it a practical choice.

Begin slowly with short walks – perhaps 5 to 10 minutes – on a level surface. Focus on maintaining good posture: head up, shoulders relaxed, and core engaged. Avoid hunching or leaning forward.

Gradually increase the duration and pace as your tolerance improves. Aim for 30 minutes of brisk walking most days of the week, but listen to your body’s signals.

Proper footwear is vital. Choose supportive shoes with good cushioning to absorb impact. Consider using walking poles for added stability and reduced spinal load.

Pay attention to any pain signals. If walking exacerbates your symptoms, reduce the intensity or duration, or consult your healthcare provider.

Water Aerobics

Water aerobics presents an exceptionally gentle and effective exercise option for those with spinal stenosis, leveraging the buoyancy of water to minimize stress on the spine and joints. The water supports your weight, reducing impact and allowing for a greater range of motion.

Classes are often available at local gyms or community centers, guided by instructors experienced in adapting exercises for various conditions. Alternatively, simple exercises can be performed independently.

Focus on movements like walking or jogging in the water, arm raises, and leg lifts. The water resistance provides a natural strengthening effect without excessive strain.

Warm water (around 85-90°F) is ideal, as it helps relax muscles and further reduce discomfort. Ensure the water depth allows you to stand comfortably with your head above the surface.

Listen to your body and avoid any movements that aggravate your symptoms. Water aerobics offers a safe and enjoyable way to improve fitness and manage spinal stenosis.

Exercises to Avoid

Individuals with spinal stenosis should avoid exercises that excessively flex, extend, or twist the spine, as these movements can exacerbate nerve compression and pain. High-impact activities like running, jumping, and heavy lifting are generally not recommended.

Deep forward bending, such as touching your toes, can worsen symptoms, particularly in lumbar stenosis. Similarly, prolonged sitting or slouching can increase pressure on the spinal nerves.

Avoid exercises that involve repetitive twisting motions, like certain yoga poses or golf swings, as they can irritate the spinal structures. Exercises causing radiating pain down the legs should be immediately stopped.

Caution is advised with overhead activities that hyperextend the neck, especially in cervical stenosis. Always prioritize maintaining proper posture and avoiding movements that provoke discomfort.

Consulting a healthcare professional is crucial to determine a safe and effective exercise program tailored to your specific condition and limitations.

Resources and Further Information

For comprehensive information on spinal stenosis and exercise, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) provides detailed resources at www.ninds.nih.gov. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) offers patient education materials at orthoinfo.aaos.org.

Numerous PDFs detailing exercises for spinal stenosis are available online, but always verify the source’s credibility. Look for resources created by qualified healthcare professionals or reputable medical institutions.

WebMD (www.webmd.com) and Mayo Clinic (www.mayoclinic.org) offer accessible articles and videos explaining the condition and management strategies.

Consider exploring patient forums and support groups for shared experiences and advice, but remember that online information should not replace professional medical guidance.

Always discuss any new exercise program with your doctor or physical therapist to ensure it’s appropriate for your individual needs and condition.